Danielle Smith-Llera’s Che Guevara’s Face: How a Cuban Photographer’s Image Became a Cultural Icon (2016) is one of a series of books aimed at secondary school readers analysing individual photographs. Smith-Llera examines Alberto Korda’s famous image of Che within its cultural and political context, tracking its history from his taking and editing it, as it took on a life of its own to become one of the most recognizable images of the 20th century.

Korda started his career as a fashion photographer in the early 1950s, working for various magazines and newspapers, including Vogue, but he supported the Cuban Revolution. In 1959, he became an official photographer for the new government and Castro’s photographer of choice. Working with a Leica M2, he documented the Cuban Revolution and its aftermath.

The photograph of Che came about because of an act of sabotage. Two massive explosions had occurred in Havana Harbour on 4 March 1960 while weapons and ammunition intended for the Cuban armed forces were being unloaded from the French ship La Coubre. Some 100 people were killed and hundreds more injured.

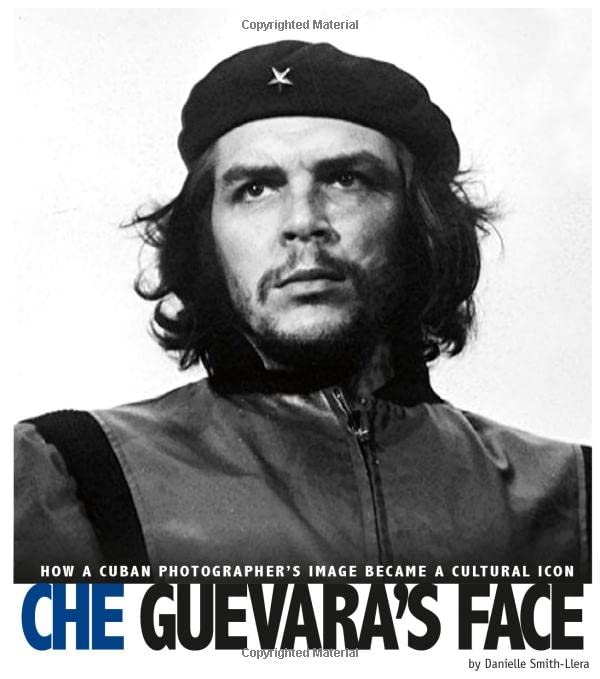

Guerrillero Heroico (Heroic Guerrilla), as Korda called it, was taken the following day at a memorial service for victims of the explosion while Che was listening to a speech by Castro. Korda, on assignment for the newspaper Revolución, was photographing Castro as he spoke, as well as Simone de Beauvoir and Jean-Paul Sartre who were present on the stage.

Korda noticed Che in the crowd and took two photographs, one vertical, the other horizontal. The vertical one had someone’s head over Che’s shoulder, so drawing on his fashion background, Korda cropped the horizontal one to exclude extraneous details – a face in profile to the left and palm fronds to the right – leaving Che isolated against the sky and giving the result a stylised look the original does not possess.

Despite its subsequent fame, the photograph did not make the next day’s paper: the editor chose Castro and the French visitors. However, Korda pinned Che to his studio wall, no doubt seeing something special in it, and sometimes gave copies to visitors. It first appeared in print in April 1961 as part of an announcement in Revolución for a talk Che planned to give, then outside Cuba after Che’s murder in 1967.

Guerrillero Heroico took on a life of its own following Che’s death. Italian millionaire publisher Giangiacomo Feltrinelli distributed copies through his bookshops, tapping into the public outrage, and the image was further edited by artists, continually manipulating the original into the form with which we are familiar. Yet while it has been seen as a symbol of rebellion, socialism, and anti-imperialism, it has also been criticised as overly simplistic and romanticising a controversial figure who played a key role in the brutal suppression of the new regime’s opponents.

Despite the ambiguities surrounding Che’s legacy, the photograph’s commercial potential was quickly realised, both by the Cuban government desperate for hard cash and by entrepreneurs around the world, utilising the image to sell products and making it a popular icon. Korda ignored this appropriation, happy to see the image used, though he was not given credit or paid royalties. His attitude changed in 2000 when it was used to sell vodka. Cuba only signed the Berne Convention in 1997, finally bringing copyright laws to the island. Korda was able to assert his rights over his intellectual property and successfully sued the company.

Korda’s other notable works include portraits of the Cuban people and landscapes, as well as photographs of political leaders and cultural figures from around the world. But with little gratitude for his service to the Revolution, Korda’s studio was raided in 1968 during a crackdown on small business and most of his archive confiscated. He turned his attention from politics to underwater photography and had a major exhibition in Japan.

There was far more to Korda’s output than this photograph, and one wonders if he felt it overshadowed the rest, the reason he downplayed its significance; if so, it was in vain. After his death in 2001, his daughter continued to protect his intellectual property while members of Che’s family criticised some of the products to which it has been attached. The two families are though symbiotically linked, Che and Korda each helping to keep the fame of the other alive.

The book includes background on Che, the history of Cuba and the course of the Revolution, concluding with a basic timeline, glossary, resource list, critical thinking questions, notes and bibliography. It is extensively illustrated. While a useful addition to the growing literature devoted to Che, despite the use of icon in the subtitle it doesn’t deal with his meditative pose as a devotional object. That click of the shutter was, in time, to cement Che’s position as a martyr.