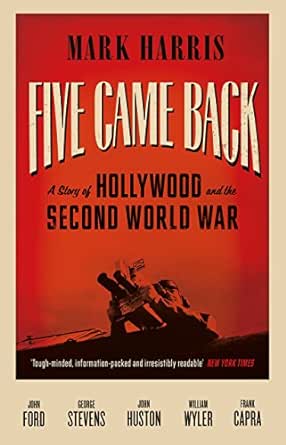

Mark Harris’s Five Came Back (2014) explores the experiences of five prominent Hollywood filmmakers – John Ford, George Stevens, John Huston, William Wyler and Frank Capra – during the Second World War. All five put lucrative careers on hold to volunteer in the service of their country and were commissioned by the United States government to make films that would support the war effort.

Before the war the US film industry faced a government monopoly investigation which threatened to break up its vertical production/exhibition model, and operated in a climate of opinion that it did not wholeheartedly espouse American values. The war laid these negative views to one side for the duration as government and studios, with a significant Jewish presence, allied to fight a common enemy. Ironically, the films of Leni Riefenstahl were seen as an indicator of the power of propaganda, acting as a stimulus for an allied equivalent.

Five Came Back is an in-depth look at these directors before, during and after the war. They were all welcomed into the services and their work was appreciated, though to an extent dealing with the military bureaucracy was not that distant from the struggles to maintain a vision of the finished product to fruition they faced inside the Hollywood system. It was understood that filmmakers were necessary to disseminate official messages and maintain morale during the difficult years ahead.

Harris examines the professional and personal struggles of the five as they navigated the challenges of balancing service to the country while maintaining their artistic integrity by producing realistic works, an effort often hampered by a reliance on elements cobbled from other projects to pad out their footage (Capra’s The Battle of China a notable but far from unique example) or restaged (Huston’s Battle of San Pietro). He provides an overview of their prodigious output, working in every theatre and with every service.

Conversely, Harris demonstrates the transformative power the war had on their lives and subsequent careers. He shows how witnessing the horrors of war impacted them psychologically (particularly Stevens, whose footage morphed from filmmaking to collecting evidence of genocide) as they readjusted to post-war civilian life. Bearing the scars of what they had experienced, they rejoined an evolving industry catering to a war-weary public.

Despite their patriotism, the consequences of their wartime efforts were not always positive: for example, Capra’s involvement with propaganda, producing the Why We Fight series, led to charges of being a government hack, which affected his reputation after the end of the war. Ford fared better with his efforts, winning two Oscars, Wyler triumphed with The Best Years of Our Lives and Stevens with Diary of Anne Frank.

While maintaining the focus on his chosen directors, Harris delves into the broader political and social climate of a period in which the liberal politics of the five were at odds with the increasingly right-wing conformist ideology being foisted on Hollywood by the House Un-American Activities Committee. His group biography allows him to explore a range of issues as pertinent today as they were then: the relationship between politics and film, the uses of censorship, the legitimacy of propaganda in a democracy, the media’s role in shaping public opinion, and how art can be used as a tool for social change.