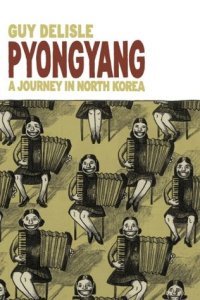

In 2005 Guy Delisle, a Canadian animator, spent two months supervising a cel animation project at the SEK studio in Pyongyang for a French company, much of the routine drawing work in the labour-intensive process having been outsourced to the Far East for cost reasons. From his experiences he produced this 2006 account of his time there, Pyongyang: A Journey in North Korea (though there was not a great deal of journeying outside the city), appropriately in graphic form.

As travel memoirs of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea are not plentiful it promised to provide illuminating insights, as far as an outsider whose movements were rigidly circumscribed would be able to describe it. Disappointingly, the result is more about Delisle than it is about North Korea. He thinks he is being smart, but he comes across as smug, patronising, with a marked sense of superiority, and a readiness to be irritated, particularly when it comes to food and customer service which do not meet his western standards.

He was probably frustrated by the inability to roam freely, accompanied as he was much of the time by a guide and translator who were there to keep an eye on him, though he knew the score before he arrived. In fact he is able go out solo occasionally, albeit the results are not particularly illuminating as he does not know the language and anyway locals are unwilling to engage with foreigners. When he sneaks off to a railway station his guides do not want him to visit he finds it looks like an ordinary railway station so the reasons for some restrictions remain obscure.

His guides do take him to various state-approved attractions, mostly glorifying Kim Il-sung and Kim Jong-il admittedly, when they could have left him sitting in his hotel room outside working hours – but thanks, and a willingness to empathise while being aware of the agenda, are in short supply. Delisle prefers snide mockery of the regime’s pretensions, makes fun of those with whom he is in contact despite the politeness they show, and prefers to spend his time socialising with other ex-pats.

The major occasion he feels comfortable with his minders is when they all go on a picnic and they sit round relaxing, just being men not representatives of different ideologies: in other words, North Korea with the Koreanness drained out. Otherwise he enjoys trying to outwit them, ignoring the potential problems it could cause them with their superiors.

There is plenty of commentary about the country’s less savoury aspects, notably obviously its rigid authoritarian structure. The Kim idolatry is laid on thick and Delisle wonders if the North Koreans actually believe the propaganda, or merely go along with it for self-preservation. They certainly seem to accept the exaggerated stories of American atrocities during the Korean war; with no independent criteria for evaluating the political system it would be difficult for them to reach an objective conclusion.

On the other hand, a chilling moment occurs when he mentions he hasn’t seen any disabled people on the streets, only to be assured that there aren’t any as all North Koreans are born ‘strong, intelligent and healthy,’ something it is hard to believe could be said with sincerity. The implication is there is a eugenics programme but nobody is willing to admit to its existence, an omission suggesting an awareness of the immorality involved.

Delisle has brought a copy of 1984 with him which he mischievously lends to his guide who wants English-language reading material. It is returned quickly, presumably because the guide has spotted echoes and is uncomfortable. However, the act of borrowing unapproved books is something Big Brother would have frowned on, so the parallel is not exact. (Delisle seems to have brought just the one book to what he knew was a place with limited leisure opportunities. What did he expect to do with his free time? Chumming with other ex-pats presumably.)

There was potential for a deeper analysis of potential cognitive dissonance, yet having touched on it Delisle forgoes further exploration; the same for the treatment of how creating an outgroup to fear (the ridiculous claim of an imminent American-backed invasion) is used to strengthen social cohesion and subservience. The presence of NGOs is surprising as an open admission of need, but apart from an enjoyment of partying by their staff we learn little about their role or how North Koreans square their presence with the success stories they are fed.

If the country really was as secretive as its popular image implies, no foreigners would be allowed in at all; in fact, my son has been to North Korea to participate in a marathon. While the place is hardly a beacon of democracy, and Kim Jong-un is undoubtedly a tyrant, on the evidence of Delisle’s brief stay it is a more complex country than it is generally depicted. Unfortunately, such hints can only be read between the lines because Delisle is firmly the major character and the North Koreans are his foils. One comes away feeling the experience was wasted on him.