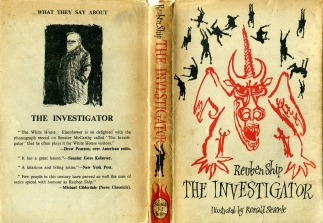

The Investigator: A Narrative in Dialogue (1956) is the lightly adapted script of a radio programme broadcast by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation in May 1954. It is a biting, and very funny, satire on the US House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC), and particularly its prime mover (a lightly disguised) Senator Joseph McCarthy. The Investigator is never named, but his identity is obvious. As the original play was only an hour long it is a fairly short book, but the satire holds up well, and an added pleasure of the printed version is provided by Ronald Searle’s illustrations.

Shortly before getting on an aeroplane the arrogant Investigator, head of a committee scrutinising the activities of the country’s citizens, is urged by committee member Garson to call off a hearing because its current target is ‘too big’. He refuses to accede, but the plane crashes and the Investigator finds himself at the gates of Heaven, or rather ‘Up Here’, to which he has to apply for entry. Should he fail, he would have to go ‘Down There’.

The arbiter is a woolly individual, The Gatekeeper, aided in an advisory capacity by a committee, members of which are the unsavoury collection of Titus Oates, Torquemada, Cotton Mather and ‘Hanging’ Judge Jeffreys. This group connives with the Investigator to oust the Gatekeeper so they can bring a more rigorous approach to the work of assessing the fitness of applicants to Up Here.

During his admission hearing the bureaucracy-savvy Investigator runs rings round the Gatekeeper with procedural motions, eventually tying him up in knots by browbeating him, to the extent the Gatekeeper resigns in frustration and the Investigator takes over as chair of the committee. Unfortunately he becomes overenthusiastic, and re-examines many of those living Up Here to see if they should be deported Down There.

These include not only obvious targets like Karl Marx (the committee keeps getting the wrong Marx before it, and in frustration the Investigator orders the eviction of all Karl Marxes) but intellectuals like Socrates, Voltaire, Milton, John Stuart Mill and Luther, even Abraham Lincoln, all of whom are thrown out. When interrogated by the Investigator they reply with quotations from their work, but despite asserting the values of liberty and freedom of thought, all are deemed guilty of contravening the narrow limits of tolerance set by the Investigator.

As the numbers of deportations grows, so does panic, with nobody wanting to be tainted by association with someone who might be convicted by the committee. The result of the mutual suspicion is the paralysis of free expression, not that it matters as even the apparently blameless fall foul of the Investigator and are banished Down There.

Eventually the boss of Down There – identified merely as the Voice – becomes agitated by the increasingly oppositional activities of the ‘crackpot reformers’ being sent to him, and appeals to the Investigator to cease the ejections. Naturally the Investigator refuses because he has immense power in his hands. Finally he wishes to bring the Chief of Up Here before the committee! That is too much even for the likes of Torquemada, Jeffreys and Oates and they protest, just as Garson had appealed to him to desist before the crash. Finally, as the Chief arrives, the Investigator loses his mind and shouts that he is the Chief.

Things have to change, and the Gatekeeper, with his relaxed admission criteria, is reinstated and the Investigator’s decisions rescinded. The Investigator is expelled, but he is not wanted Down There either. Fortunately there is a never-before-used clause in the regulations stating that if a person is refused entry Down There, that person can be returned to the border at the point they initially crossed. The Investigator is thus sent back to the land of the living, the sole survivor of the crash, but only a shell of his former self, babbling about being the Chief. The menace has been neutralised.

The print version, published in the UK by Sidgwick and Jackson, has an introduction by Ship, ‘A short history of a long-playing record’. He describes his work as a ‘satire on contemporary American witch-hunters’, so there is no doubt he considered McCarthy to be in good company with the historically repellent committee members Up Here. As the play could not be rebroadcast in the US, tapes and long-playing records soon circulated clandestinely. Ship says the records were bootleg, but he seems to be tapping his nose, and it is reasonable to infer he had some involvement in the project. The inside of the dust jacket has an advertisement for the long-playing record, released by Oriole, ‘obtainable from all record shops’ (at least in the UK).

Ship quotes the New York Times reviewer who predicted the record would kick up a political fuss, a result that would have pleased Ship. Curiously, the recordings were listened to in Washington, possibly even by President Eisenhower – Senators laughing openly according to Ship – hinting that McCarthy was being seen by some as a figure of fun. The book provided another chance to blow a raspberry and depict despotism eating itself.

Ship sees laughter as an antidote to the ‘paralysing poison of fear’, and refers to The Investigator‘s ‘barbs of ridicule’. At the same time the play draws out the fascistic undercurrent in HUAC, within which Ship had himself been caught up. Working in Hollywood, his liberal views had brought him to the attention of HUAC, and having given an unsatisfactory account of himself in their opinion, he had been deported in traumatic circumstances to his native Canada. The play settles some scores, and does it handsomely.