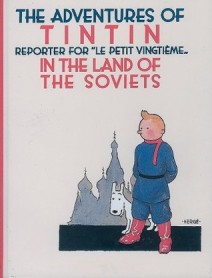

Tintin’s first adventure, Tintin in the Land of the Soviets (Tintin au pays des Soviets), was published in black and white – and betraying a black and white ideology in the writing – firstly in comic strip form from early 1929, then in book form in 1930. It is far from the polished product we are used to from Hergé’s later books.

Commissioned by his newspaper, Tintin and Snowy set off for Russia to report on the terrible conditions there; this being a strip written for the right-wing Catholic newspaper Le Vingtième Siècle, the political perspective is unambiguous. The plotting is perfunctory as Tintin staggers from one mishap to another, the charm of the later books in the series sorely lacking.

Getting to Russia from Belgium takes him via Berlin, providing Hergé the opportunity for some German stereotypes to add to the Russian ones we will meet later. Despite letting him in to Russia because his papers are in order, the Bolshevik agents go to great lengths to kill him in order to prevent him conveying news about the state of the country to his paper’s readers. They could have refused him entry, the easier option, though that probably would not have stopped the intrepid reporter.

Naturally, once inside Soviet territory he finds a repressive police state in which the Communist Party rigs the system to retain power, and ordinary people are exploited for the benefit of its leaders. The regime’s boasts to the outside world of strong Soviet productivity are lies sucked up by naïve English communists, whereas the reality is poverty and squalor. Grain is exported for propaganda purposes by bolstering the image of prosperity internationally, leading to starvation at home and the available food used as a weapon of control.

While learning the reality of what is going on, Tintin survives various attempts on him thanks to a combination of ineptitude by the Russians, a lot of luck, and his own physical indestructibility. He is happy to take opponents on in fisticuffs, including a bear, and however tight the spot naturally wins through. The OGPU operatives having failed miserably in their assassination attempts, Tintin and Snowy eventually make it back to Brussels, again via Berlin: an opportunity to defeat the Russian agents one last time and collect a big reward from the Germans.

There are some historical oddities betraying a lack of research (not that there is anything approaching a documentary feel). The introduction to the 1989 British edition notes that Hergé at one point uses the word Cheka, though the organisation had been superseded by the OGPU in 1922. Trotsky’s name is invoked as an oath, though in 1929 he was in exile, and later Tintin finds himself in the secret lair where Lenin (dead five years), Stalin and Trotsky (unlikely bedfellows) have stashed their wealth stolen from the Russian people. Such details would be unlikely to bother the readers of Le Vingtième Siècle.

The book is a combination of strong, confident, graphic style depicting energetic action, married to crude, unsubtle and tiresome propaganda, the critique of a political system blurring into racism, and Tintin far from the loveable character he became in later stories. Thank goodness for Snowy/Milou, whose observations inject much-needed humour. Lovers of the Tintin series will want to see the origins of the character, but may be disappointed by Hergé’s initial effort.