It is 1940 and the Blitz is raging, while the doctors and nurses at Heron’s Park military hospital in Kent look after their patients as best they can. The individuals who will later become either suspects or victim in a murder enquiry are introduced to the reader by means of letters the elderly postman, Joseph Higgins, is carrying to the hospital accepting positions on the staff. He will become intimately linked to them when he is caught in a bomb blast and brought into the hospital badly injured.

He dies on the operating table, which appears to be misadventure, but Inspector Cockrill of the local constabulary is requested to conduct an investigation in order to make sure everything is above board for the coroner’s report. Later a sister loudly claims to know what happened, and that it was no accident, but then she too is found dead, and this time there is no mistaking it is murder.

Cockrill has to find out who the culprit is, and why the crimes were committed. Only half a dozen doctors and nurses were in a position to carry them out, but while alibis are in short supply nobody appears to have a motive. Then an attempt is made on another in the group. Even when the inspector works out who the murderer is, he cannot determine the method used to dispatch Higgins, and without proof must rely on forcing a confession.

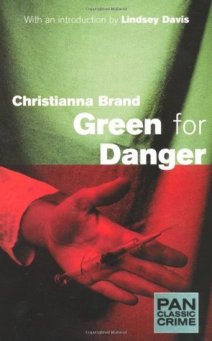

Christianna Brand’s 1944 novel is the second in the series featuring Cockrill. Alastair Sim, who played him in the film version, was tailor-made for the part, surface geniality masking hard resolve. But rather than the standard series of interrogations by the detective, much of the dialogue consists of the characters chatting to each other and discussing the weaknesses in their accounts of where they were at the critical moments.

The plot is cleverly constructed and the characters are well rounded, though the pace is leisurely. Brand’s husband was a surgeon, and the details of hospital life and medical procedures seem authentic, as does the stoicism necessary to endure both constant nightly bombardment and the tediousness of rationing.

Language is dated (lots of ‘darling’) but the novel is franker about sex than one might expect from the period, with close emotional attachments, and jealousies, forming between men and women thrown together in exceptional circumstances. Nor is it afraid to include one of the characters sending a letter to Austria (purpose not specified) and people listening to German radio broadcasts and referring to Lord Haw-Haw; all surprising for a book published during the conflict. Definitely of its time is the amount of smoking done, even on the wards.

The realistic details ground the murder mystery, which itself relies too much on luck. It also seems unlikely that, knowing a murderer was one of a small group, a detective would make them sweat by keeping them cooped up, ratcheting the tension in the hope the guilty one cracks. Cockrill is able to devote considerable person-hours by assigning subordinates to keep close watch on the group when there is rather a lot for them to do, thanks to the Luftwaffe, with no certainty his unorthodox method will work.

Of course the murderer is unmasked, though Cockrill would argue that justice is not served. An epilogue follows up the other suspects later, showing that, as in the real world, not everybody is happy ever after.